Why I think open peer review benefits PhD students

Should peer review be blind?

Should peer review be blind?

Doing scientific research is my dream job. Unfortunately, it’s not at all certain that I can keep doing research after getting my PhD degree. Research jobs are scarce and every year the academic job market is flooded with freshly minted PhDs. In practice, this means that only the most prolific PhD students will land a job. In other words, you either ‘publish or perish’. In this blog post I will argue that the culture of ‘publish or perish’, although not a problem in theory, is a problem in practice because of the unfairness of the peer review system. In my view, opening up this system would make it fairer for all researchers, but especially for PhD students.

Based on discussions with colleagues as well as my own experiences I’ve become aware that the peer review system can be random and biased. This intuition is supported by scientific studies of peer review that find that the interrater reliability of reviewers is low, which means that an editor’s (often arbitrary) choice of reviewers plays a big part in whether your manuscript will be accepted (Bornmann, Mutz, & Daniel, 2010; Cicchetti, 1991, Cole, Cole, & Simon, 1981; Jackson, Srinivasan, Rea, Fletcher, & Kravitz, 2011). In addition, studies have found that reviewers are more likely to value manuscripts including positive results (Mahoney, 1977; Emerson et al., 2010) and results consistent with their theoretical viewpoints (Mahoney, 1977). These structural biases as well as the random element make the peer review system unfair as it is unable to consistently distinguish good quality research from bad quality research. This is especially concerning for PhD students who only have a few years to accrue publications to get funding for an academic job. One unfair negative review could nip their career in the bud.

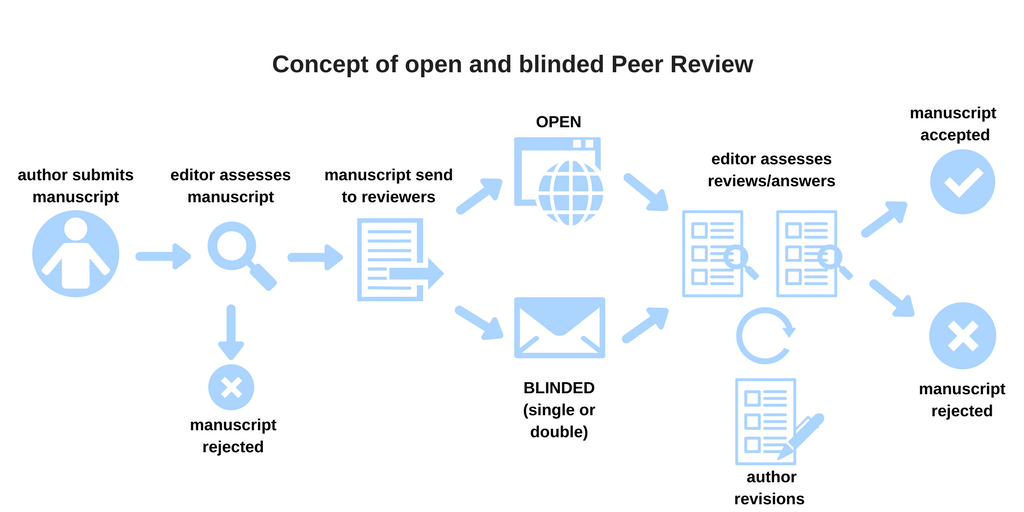

In my view, the solution to the unfairness of the peer review system is straightforward: Switch from a closed peer review system to an open peer review system. Here, I define open peer review as a peer review system in which authors and reviewers are aware of each other’s identity, and review reports are published alongside the relevant article. Ross-Hellauer (2017) found that these two aspects together account for more than 95% of the mentions of ‘open peer review’ in the recent literature. Note that open peer review may also refer to a situation where the wider community can comment on a manuscript, but I do not use that definition here. Below, I list the potential benefits and downsides of switching to an open peer review system.

Potential benefits of open peer review for PhD students

- In an open peer review system reviewers’ names are linked to their public reviews, which increases accountability.

This accountability may cause reviewers to be more conscientious and thorough when reviewing a manuscript. Indeed, a transparent peer review process has been linked to higher-quality reviews in several studies (Kowalczuk et al., 2015; Mehmani, 2016; Walsh, Rooney, Appleby, & Wilkinson, 2000; Wicherts, 2016), although a sequence of studies by Van Rooyen (Van Rooyen, Delamothe, & Evans, 2010; Van Rooyen, Godlee, Evans, Smith, & Black, 1999) failed to find any difference in quality between open and closed reviews. For PhD students higher quality peer reviews are especially important because they are at a stage where feedback on their work is crucially important for their development. Moreover, high quality reviews are fairer for PhD students as such reviews can distinguish more accurately between good and bad research (and thus good and bad PhD students).

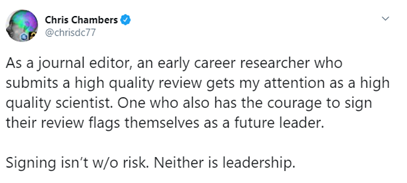

- If the identity of reviewers are made public PhD students can get credit for the reviews they conduct.

McDowell, Knutsen, Graham, Oelker, & Lijkek (2019) found that many PhD students do not find their names on peer review reports submitted to journal editorial staff even though they had co-written the report with a more senior researcher. In such instances of “ghostwriting” the PhD student usually does most of the work while the senior researchers is the only one that profits by gaining appreciation from the editor. An open review system would provide public credit to reviewing PhD students (for example by making reviews citable, Hendricks & Lin, 2017) but would also provide less tangible rewards like senior researchers acknowledging their skills as a high quality scientist (see tweet below).

- The fact that reviews are made open may also create a motivation for reviewers to be more friendly and constructive in their reviews.

Of course, this would greatly benefit PhD students because given their status they are likely influenced most severely by scathing or harsh reviews. Indeed, some research shows that reviews are potentially more courteous and constructive when they are open (Bravo, Grimaldo, López-Iñesta, Mehmani, & Squazzoni, 2019; Walsh, Rooney, Appleby, & Wilkinson, 2000).

- Open peer review may lessen the risk of PhD students publishing in predatory journals.

In a situation with open peer review, journals with no or substandard peer review will be identified quickly and will become known as low-quality journals. Predatory journals can no longer hide behind the closed peer review system and will eventually disappear. This makes life easier for PhD students as it is often difficult to orient the publishing landscape if you are inexperienced with it.

- Open peer review can help to prevent a practice called citation manipulation (Baas & Fennell, 2019), whereby a reviewer suggests large numbers of citations of their own work to be added to a submitted manuscript.

These are often unwarranted citations, but researchers (especially PhD students) are often coerced into adding them because they desperately want to publish their paper. Of course, only researchers who have a reasonable amount of citable papers under their belt would engage in citation manipulation, making it harder for PhD students to compete on the academic job market. Indeed, a prominent case of citation manipulation spurred a group of early career researchers to write an open letter to voice their concern. Open peer review would clearly help here as reviewers thinking of engaging with this unethical practice would think twice if their name and review were public.

- Open peer review provides PhD students with insight in the mechanics of science.

For example, it allows PhD students to see how other papers have developed over time or to see that landmark papers have been rejected multiple times before being published. Such insights into the peer review process are very valuable for PhD students as they can get more comfortable with the peer review system and can see that rejections are the norm rather than the exception.

- Open peer review (or streamlined review, see Collabra, 2019) could save PhD students (and other researchers) time.

Once a manuscript is rejected it is usually sent out to another journal to undergo a new round of review. It is likely that the arguments used by the first set of reviewers and the second set of reviewers are similar because the first set of reviews was done behind closed doors and authors often change little in between submission. It is estimated that 15 million hours are spent every year by restating arguments while reviewing rejected papers (The AJE Team, 2019). In open peer review, researchers can build on previous reviews, and see the development of the paper, which can free up many hours for valuable research. Of course, not all of the wasted review time is accounted for by PhD students, but because they are likely taking longer than the mean 8.5 hours for a review (Ware, 2008) an open peer review system would be especially time-saving for them.

Potential downsides of open peer review for PhD students

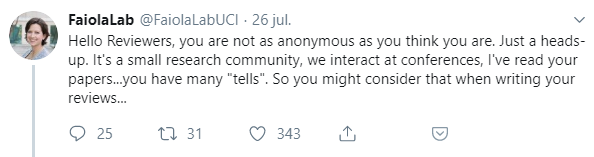

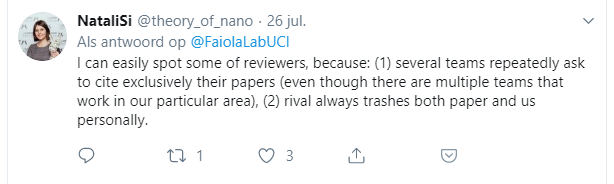

- The main argument put forward against open peer review is that PhD students who write negative reviews may frustrate other researchers who could then retaliate. For example, vindictive researchers could provide negative reviews of the PhD student’s future work or could speak badly about them to their colleagues during a conference or in personal e-mails. This is plausible, but it is unsure whether a blind review system would prevent such practices as anonymity is by no means guaranteed. Many authors at least think they are able to correctly identify their reviewers (see tweets below), and a review found that masking reviewers’ identities was only successful about half of the time (Snodgrass, 2006). In any case, open peer review at least makes situations of power abuse easier to identify.

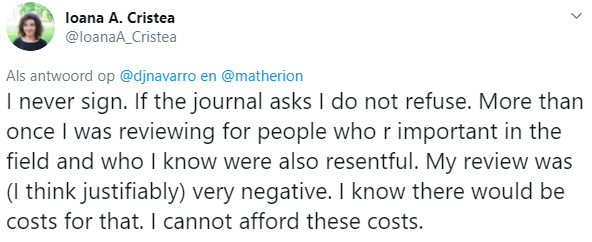

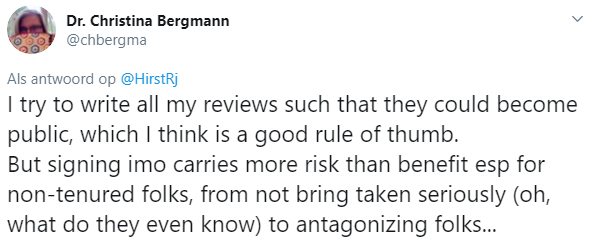

- Whether PhD students will be retaliated against or not, a fear of retaliation does exist in the academic community (see tweets below) This fear could cause PhD students to shy away from criticizing senior researchers in reviews, or could even cause PhD students to reject review requests for work authored by senior researchers. The first scenario would cause suboptimal work by senior research to be published more often, reinforcing the academic status quo and decreasing the quality of the scientific literature. The second scenario would prevent PhD students from gaining valuable review experience and would cause the scientific process to slow down. The second scenario seems unlikely though in light of findings by Bravo et al. (2019) and Ross-Hellauer, Deppe, & Schmidt (2017) that more junior scholars are more willing to engage in open peer review than more senior scholars.

- Power dynamics can also play a problematic role when the reviewer is a senior researcher and the manuscript’s author is a PhD student. When the manuscript involves findings that run counter to the senior researcher’s self-interest they may decide to write a condemning review to intimidate the PhD student from pursuing the work further (see tweet below). However, this can also happen in a system of closed peer review. At least in open peer review unfairly harsh and power-abusive reviews can be identified and be followed up on. Although there is currently no system for reprimanding power abuse in peer reviews, Bastian (2018) argues that there are ways to do this effectively. For example, we could explicitly label power abuse in peer review as professional misconduct or even harassment in the relevant codes of conduct.

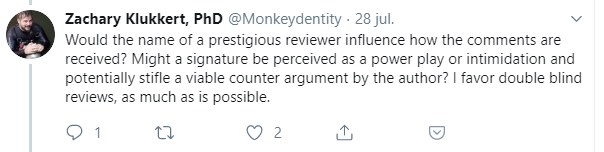

- In my view, the most problematic downside of open peer review (as I have defined it) is that all kinds of biases could creep into the peer review system. For example, it could be the case that papers from PhD students are rejected more often because PhD students do not have enough prestige or because PhD students more often come up with ideas that challenge the status quo in the literature. And indeed, studies have shown that open peer review may be associated with disproportionate rejections of researchers with low prestige, like PhD students (Seeber & Bacchelli, 2017; Tomkins, Zhang, & Heavlin, 2017). These findings are worrying and should be taken seriously. Importantly, open peer review should not be a goal in itself but should only be implemented when the benefits outweigh the costs. In this case, the benefits of unmasking the identities of authors (e.g., less hassle with masking your manuscripts) are marginal while the potential costs (discrimination against low prestige researchers) are likely high. An open peer review system where the identities of authors are masked therefore seems like the best solution.

Conclusion

My hope is that I won’t be the one to perish, but the simple fact is that there’s not enough funding available to accommodate every PhD student aspiring a job in academia. That does not need to be a problem as a little academic competition is fine. After all, it only seems fair that the best of the best are tasked with expanding our scientific knowledge. However, the best of the best are only selected as long as the peer review system is fair. Currently, that does not seem to be the case.

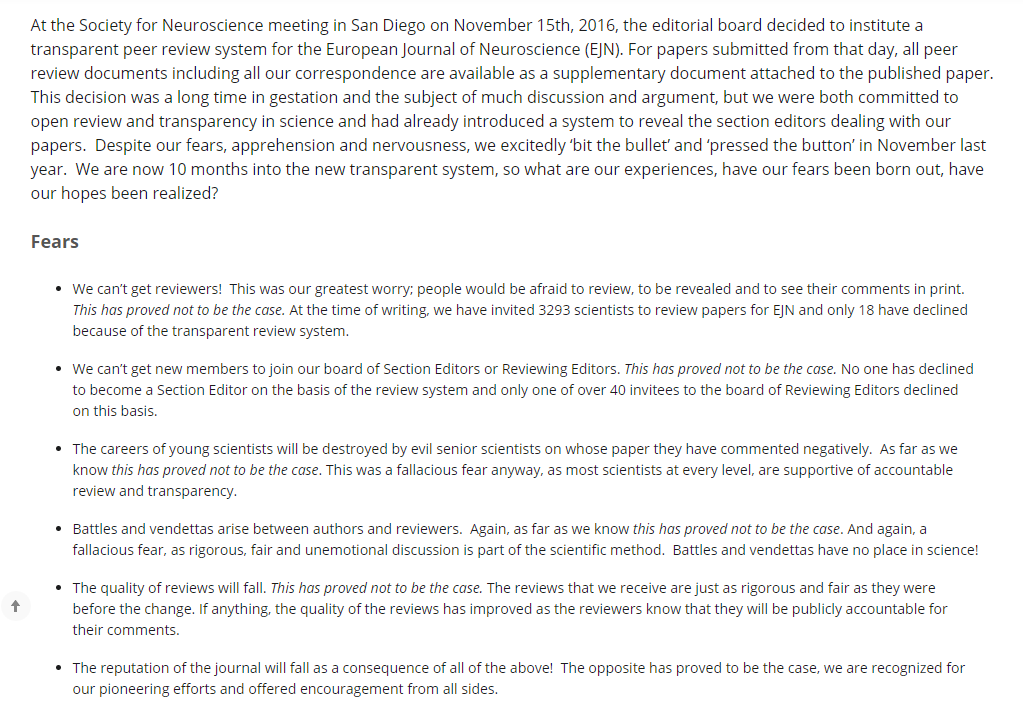

In this blog post I have therefore argued for an open peer review system. Implementing this system across the board could increase the quality and tone of peer reviews, could provide PhD students with credit for their reviews, could root out predatory journals, could prevent citation manipulation, could provide PhD students with insight into the mechanics of science, and could lessen the peer review burden for PhD students. Even though the arguments against open peer review should be taken seriously (for example by masking the identities of authors) I am convinced open peer review will create a fairer system. And, as you can see below, the European Journal of Neuroscience, one of the journals that already practices open peer review, wholeheartedly agrees.

Excerpt from the summary report of the European Journal of Neuroscience about their new open peer review system. Retrieved from https://www.wiley.com/network/researchers/being-a-peer-reviewer/transparent-review-at-the-european-journal-of-neuroscience-experiences-one-year-on

References

Baas, J., & Fennell, C. (2019, May). When peer reviewers go rogue-Estimated prevalence of citation manipulation by reviewers based on the citation patterns of 69,000 reviewers. SSRN Working Paper. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3339568.

Bastian, H. (2018). Signing critical peer reviews & the fear of retaliation: What should we do? https://blogs.plos.org/absolutely-maybe/2018/03/22/signing-critical-peer-reviews-the-fear-of-retaliation-what-should-we-do.

Bornmann, L., Mutz, R., & Daniel, H. D. (2010). A reliability-generalization study of journal peer reviews: A multilevel meta-analysis of inter-rater reliability and its determinants. PloS ONE, 5(12), e14331.

Bravo, G., Grimaldo, F., López-Iñesta, E., Mehmani, B., & Squazzoni, F. (2019). The effect of publishing peer review reports on referee behavior in five scholarly journals. Nature Communications, 10(1), 322.

Cicchetti, D. V. (1991). The reliability of peer review for manuscript and grant submissions: A cross- disciplinary investigation. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 14(1), 119-135.

Cole, S., & Simon, G. A. (1981). Chance and consensus in peer review. Science, 214(4523), 881-886.

Collabra (2019). Editorial Policies. Retrieved from https://www.collabra.org/about/editorialpolicies/#streamlined-review.

Emerson, G. B., Warme, W. J., Wolf, F. M., Heckman, J. D., Brand, R. A., & Leopold, S. S. (2010). Testing for the presence of positive-outcome bias in peer review: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(21), 1934-1939.

Hendricks, G., & Lin, J. (2017). Making peer reviews citable, discoverable, and creditable. Retrieved from https://www.crossref.org/blog/making-peer-reviews-citable-discoverable-and-creditable.

Jackson, J. L., Srinivasan, M., Rea, J., Fletcher, K. E., & Kravitz, R. L. (2011). The validity of peer review in a general medicine journal. PLoS ONE, 6(7), e22475.

Kowalczuk, M. K., Dudbridge, F., Nanda, S., Harriman, S. L., Patel, J., & Moylan, E. C. (2015). Retrospective analysis of the quality of reports by author-suggested and non-author-suggested reviewers in journals operating on open or single-blind peer review models. BMJ Open, 5(9), e008707.

Mahoney, M. J. (1977). Publication prejudices: An experimental study of confirmatory bias in the peer review system. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1(2), 161-175.

McDowell, G. S., Knutsen, J., Graham, J., Oelker, S. K., & Lijek, R. S. (2019). Co-reviewing and ghostwriting by early career researchers in the peer review of manuscripts. BioRxiv, 617373.

Mehmani, B. (2016). Is open peer review the way forward? Retrieved from https://www.elsevier.com/reviewers-update/story/innovation-in-publishing/is-open-peer-review-the-way-forward.

Ross-Hellauer, T. (2017). What is open peer review? A systematic review. F1000Research, 6. 10.12688/f1000research.11369.2

Ross-Hellauer, T., Deppe, A., & Schmidt, B. (2017). Survey on open peer review: Attitudes and experience amongst editors, authors and reviewers. PLoS ONE, 12(12), e0189311.

Seeber, M., & Bacchelli, A. (2017). Does single blind peer review hinder newcomers? Scientometrics, 113(1), 567-585.

Snodgrass, R. (2006). Single-versus double-blind reviewing: an analysis of the literature. ACM Sigmod Record, 35(3), 8-21.

The AJE Team (2019). Peer Review: How We Found 15 Million Hours of Lost Time. Retrieved from https://www.aje.com/arc/peer-review-process-15-million-hours-lost-time.

Tomkins, A., Zhang, M., & Heavlin, W. D. (2017). Reviewer bias in single-versus double-blind peer review. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(48), 12708-12713.

Van Rooyen, S., Delamothe, T., & Evans, S. J. (2010). Effect on peer review of telling reviewers that their signed reviews might be posted on the web: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 341, c5729.

Van Rooyen, S., Godlee, F., Evans, S., Smith, R., & Black, N. (1999). Effect of blinding and unmasking on the quality of peer review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14(10), 622-624.

Walsh, E., Rooney, M., Appleby, L., & Wilkinson, G. (2000). Open peer review: A randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 176(1), 47-51.

Ware, M. (2008). Peer review in scholarly journals: Perspective of the scholarly community–Results from an international study. Information Services & Use, 28(2), 109-112.

Wicherts, J. M. (2016). Peer review quality and transparency of the peer-review process in open access and subscription journals. PLoS ONE, 11(1), e0147913.